Fundamentals of Inpatient Care of Surgical Patients

VBMC TRAUMA CARE SERVICES GUIDELINE

FUNDAMENTALS OF INPATIENT CARE OF SURGICAL PATIENTS

The goal of the Trauma/Acute Care Surgery service is to provide cost-effective, high-quality patient care. To achieve this goal a customer service model has been implemented. The physician/nurse team will make excellent patient care the focus of their effort. This will be accomplished by application of “best practice” models using evidence based clinical data. This will allow the physician/nurse team to direct ancillary services in the most cost-effective manner for excellent patient care.

General Guidelines for Patient Care

The

very best way to care for patients is to understand physiology and

pathophysiology. This allows the clinician to understand the treatment being

rendered. In general, if it sounds stupid, it is stupid! Remember that every

beneficial intervention also has the potential to cause harm. When a treatment

or intervention is no longer required discontinue the intervention/treatment.

Nasogastric tubes are useful for gastric decompression and to prevent emesis

associated with bowel obstruction. On the other hand, the tubes are

uncomfortable and predispose the patient to sinusitis, GERD, and aspiration.

Proton pump inhibitors and H2 antagonists reduce the incidence of stress

ulceration. However, they are associated bacterial overgrowth in the stomach

that may lead to nosocomial pneumonia. IV catheters and fluids can be lifesaving,

but they are also associated with thrombophlebitis and infection. Foley

catheters may be needed for urinary retention or monitoring of intake and

output. However, they are associated with urethral strictures and infections.

Phlebotomy for blood tests is a necessary part of patient care. However, excess

phlebotomy can and does result in anemia that can be harmful to patients.

Medications are extremely important for patient care, but drug interactions and

adverse reactions can be harmful to patients. These are a few examples of the myriads

of rather simple interventions and therapies that can and do harm patients.

Modern medical care is exceedingly expensive. Ask yourself why a particular

intervention, test, or medication is being used. Is this needed? How does this

benefit the patient? What is the harm? How much is this going to cost? What

information will I gain? Through rigorous self-examination the answer for many

of these questions is easier than you think.

Mobilization

There

is clear, irrefutable evidence that extended bed rest is harmful to patients.

Supine position and lack of mobilization leads to reductions in pulmonary

functional residual capacity, atelectasis, diminished cough, and accumulation

of dependent lung water. This makes the patient more prone to pulmonary

complications which are the most frequent cause of admission or readmission to

the ICU. Bed rest also leads to rapid loss of muscle mass leading to

de-conditioning which may increase hospital length of stay, lengthen

rehabilitation, or create the need for rehabilitation that would have not been

otherwise needed. Patients at bed rest are more prone to pressure ulcers, bowel

dysfunction, and venous thromboembolic disease.

A

primary focus of patient care should be early mobilization of the patient.

Weight-bearing status should be determined within 24 hours of admission to the

hospital and documented in the Mobility Order Set. Ambulation of the patient

should be an immediate goal, using the Mobility Plan of Care. If there are

limitations on weight-bearing these should be identified and appropriate

resources (physical therapy, equipment, etc) should be applied immediately. At

the very least, patients should be out of bed and placed in a chair in the

upright position. This does not mean bringing the bed into a sitting position

but actually getting the patients out of the bed into a chair or at least sitting

upright on the bedside. If traction or hemorrhage risk mandates bed rest, the

patients should be nursed with the head of the bed elevated at least 30

degrees. When strict logroll is in place the patient should be placed in

reverse Trendelenburg.

Mobility

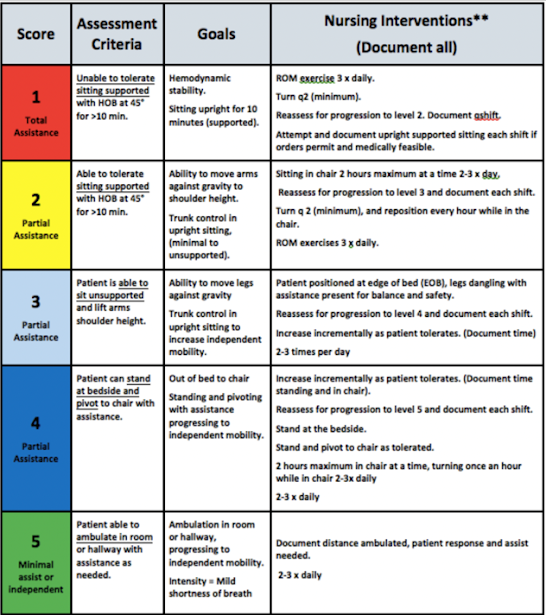

Nurse Driven Mobility Scale

Our Goal: Early progression to the patient’s best possible mobility

Please reference General Mobility and Ortho/Trauma/Spine guidelines and order set for specific instructions

Respiratory Function

Respiratory

therapy is essential for acutely ill and injured patients. Many of our patients

have co- morbid lung disease and/or a history of heavy tobacco use. Lung

function is further compromised by bed rest, obesity, chest wall trauma, pain,

surgical incisions, chest tubes, or via the use of cervical collars, back

braces, and/or traction. It is unrealistic to expect respiratory therapy

service to assume this task for most patients. Pulmonary toilet should be a

major goal for excellent nursing care.

Prevention is the key element here.

Apply

vigorous pulmonary toilet early! Use the respiratory therapist wisely. It is

far easier to prevent respiratory failure than to treat the consequences.

Patients also require education as to their role in pulmonary toilet. Patients

often equate pain with further damage. They need to understand that pulmonary

toilet may cause pain but not harm. The simplest and best pulmonary toilet is

to mobilize the patient. This requires patient effort resulting in work of

breathing that maintains respiratory muscle function. Mobilization also shifts

lung water, increases lung functional residual capacity, and reduces

atelectasis. Mobilization should be supplemented with education on maximum

voluntary ventilation, as well as coughing and deep breathing. Spirometers

(incentive spirometers, ‘blow bottles’) can and should be used to supplement

coughing and deep breathing. Some patients may require bronchodilators and/or

chest physiotherapy. Occasionally expectorants are also required. Some patients

may require nasotracheal suctioning. Pain control is essential. Patients should

be comfortable but not so somnolent that they can’t actively participate in

pulmonary toilet.

A word about supplemental oxygen

Supplemental

oxygen is expensive and unnecessary for most patients. Oxygen does not improve

respiratory failure! In fact, supplemental oxygen usually masks worsening

respiratory function that would respond to pulmonary toilet. Virtually all

human beings have arterial desaturation when recumbent or sleeping. Spot pulse

oximetry in these circumstances is of no clinical value and frequently results

in unnecessary application of supplemental oxygen. Respiratory rate and effort

combined with auscultory findings, radiograph, and subjective patient

complaints are much better determinants of respiratory failure than arterial

desaturation. In the latter circumstance, supplemental oxygen should be used

along with pulmonary toilet.

Intravenous Access

Three

quarters (75%) of all hospital bactermia events are associated with intravenous

catheters! There is a general hospital wide practice to “heparin lock” and keep

both peripheral and central venous catheters. Keeping multiple IV sites is

simply not a good practice. Every IV site represents a potential nosocomial

infection site for patients. Both insertion technique and indwell time

influence subsequent thrombophlebitis. Many catheters are placed under less-than-ideal

conditions and should be removed as soon as possible. In all but the most

unusual circumstances, a patient will require a single functioning IV access

site. Proper inspection, site care and hub cleansing should be used to maintain

function and sterility. All other intravenous access sites should be removed.